Arrived in Paris this afternoon after a quick and easy journey on the train from London.

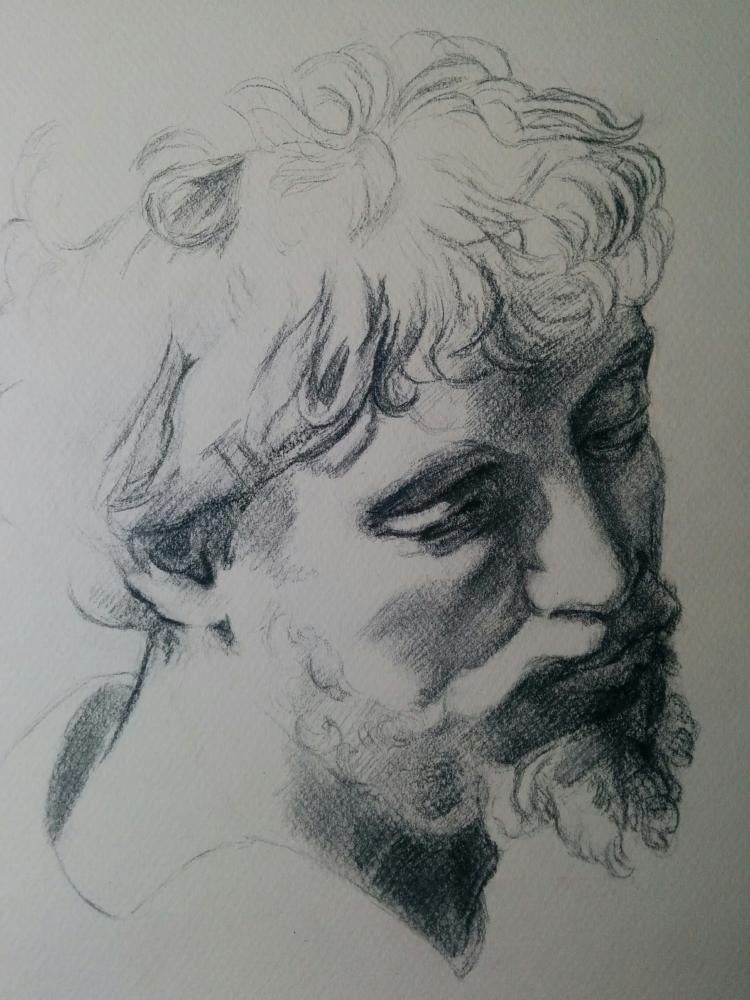

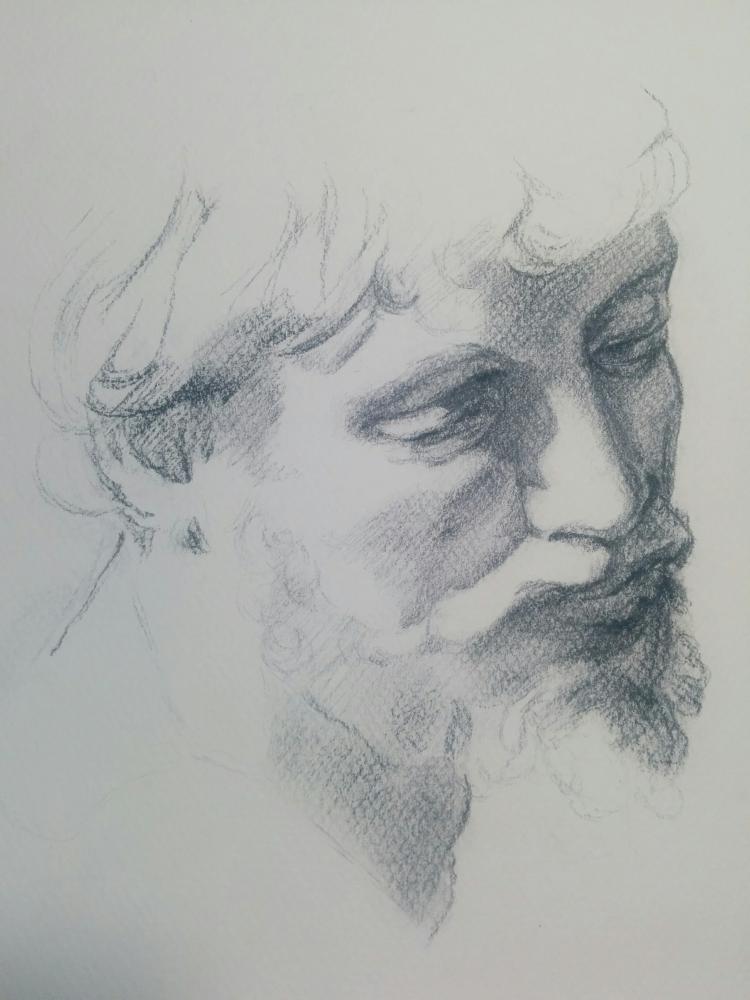

Did another quick pen and ink study tonight, this time after Tiepolo's Neptune. It's a beautiful drawing, and in its ruggedness and power it reminds me of Giambologna's terracotta bozzetto for his colossus in Pratolino. My attempt falls far short of the mark, both in terms of the drawing accuracy and the technique, but it's lovely to experiment with something new.

How did Tiepolo get such an even wash of colour, yet articulate the edges of the shadow shape so intricately? It's incredible! The ink is drying so fast, you have just a few seconds to work it into place. The entire wash over the body and leg was laid down in one go, and simultaneously the edges of the leg and the edges of the shoulder were also defined whilst it was still wet. It must have taken under a minute! I'd love to know how he did it. Mine is a mess of layers and failed articulations. Also for some reason the ink yellows the paper, again I don't know why. So much to learn.

This morning I woke up thinking about the pen and about interleaving curves of the hair and about the sharpness of the lines. I was thinking how much of a living thing an ink wash drawing is compared to chalk and charcoal. You have to work whilst the ink is wet. The nib holds only certain amount before it needs to be recharged, and the more you draw the lighter the lines become, and you have to be aware of how this affects the drawing. Just as you are running out of ink you can do the most delicate lines, the lines in the light of the form. There is a constant pressure to make marks, to make decisions before the ink dries, whereas with chalk you have all the time in the world. For some reason it makes me feel like you are creating a living thing, there is time-pressure, and there is feedback between you and the drawing. You have seconds to play with, and your marks once made cannot be erased or moved, only what you do afterwards can be changed to respond to what has gone before.

Very much living and breathing art at the moment, and I'm loving it.

I've been thinking a lot about how confidently Raphael commands individual strokes of the chalk in the portrait I've been working on. Being able to execute a complex curve in one stroke, varying its weight smoothly from light to heavy, sharp to broad, is real virtuosity. Getting it right first time, every time.

I want to get there, or at least try to, and I think using a more unforgiving medium will help train me to really think about every mark and try to get everything right first time. With pencil and chalk there is always the option to erase, to build up multiple attempts to one approximation of what should be correct. So I've bought some drawing ink and have made my first attempt at drawing with pen and ink. It's abominable, malproportioned and ugly, but I've learned something and enjoyed trying something new. Need the right paper so the water wash doesn't lift the colour and need to concentrate on the whole just as much as the individual line qualities. So much going on. It's a drawing after the peerless Rembrandt. Even more respect for his craft now.

There's also something wonderful about the feel of a sharp needle-thin steel nib on paper, leaving such a fragile and yet strong, indelible line behind. And ink washes? Wow, you can do so much in a few brief seconds, laying down so much tone and volume. I have a new respect and interest for artists like Tiepolo who worked in pen and ink, its extremely challenging.

I've been very depressed by the lack of interest in my online store for my drawings (despite paid online advertisements!), so in a fit of impetuousness I have booked a train to Paris as a distraction. I'm now deliriously excited by the prospect of the Louvre and the Musée d'Orsay. I'm just in time to catch the Parmigianino drawing exhibition, which is an excellent stroke of luck. It'll be wonderful to compare his draughtsmanship with the fresh memories I have of Andrea del Sarto's drawings I saw a couple of weeks ago.

I don't know to what ultimate end all of this is for if no-one is interested in buying drawings any more, but it gives me pleasure and I'm sticking to it, even though there seems to be no prospect of making money from it all. Such a shame that drawing, which takes so much time (and therefore money) to learn, is not a career that has been voted for by capitalism.

Still working away on my Raphael copy. What is noticeable as I'm doing it is how carefully articulated his lines are. A stroke of hair is a sinusoidal bend, an s-curve executed flawlessly in one movement. It's much harder to do than it looks, and I usually end up doing multiple strokes to get the same shape, but lose the tapering line weight as a result.

I've more or less finished the Master Art website where I will be trying to sell my drawings. I'm experimenting with paid advertising I'm praying the investment will pay off.

God keep me from ever completing anything. This whole book is but a draught—nay, but the draught of a draught. Oh, Time, Strength, Cash, and Patience! Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

Cash! Patience! In need of both at the moment. I am hoping to monetize my art, and am in the process of setting up a website to sell these drawings. Must be mindful of Leonardo's advice to not get distracted by the money though. Still, I'd rather be making money from art than anything else.

I've started listening to the audiobook of Moby-Dick, which I am enjoying immensely. Reminding me of Heart of darkness and vast unknowable nature. A good yarn, and poetical.

I'm working on a drawing by Raphael that sold a couple of years of ago for nearly £30 million. It's his Head of a young apostle. I feel a goodly amount of dread and trepidation in working from it. Such surety, sculptural simplicity and grace is so clumsily mangled by my novice hands. But it also feels good to be confronted by my own shortcomings, it gives me something to strive for. Leonardo said as much:

A painter who has no doubts about his own ability will attain very little. When his work exceeds his judgement, the artist learns nothing. But when his judgement is superior to his work, he will never cease to improve unless his love of money interferes or retards his progress” Leonardo da Vinci, A Treatise on Painting

I love the way this drawing emerges from lines shaded in one direction with such delicate, deliberate attention, self-consciously proclaiming that, yes, this is a drawing, a work of art and design, a product of contemplation and choice and decision and skill. It reveals to you how the magic trick works, but rather than spoil the show it heightens your appreciation of the mastery needed to pull it off. This is in contrast to the photo-realistic graphite and charcoal drawings that people slavishly copy from photos these days (and I've done it myself plenty of times), which seem to lack this level of self-awareness. They smudge and blend and highlight with erasers in an attempt to perfectly reproduce what the camera has already captured. They try to hide from what they are (a drawing) and try to be something else (a photo), whilst Raphael actively shows off the artifice of his art, inviting you to admire the deliberation with which his drawing is constructed and to understand and enjoy his control and judgement and ability.

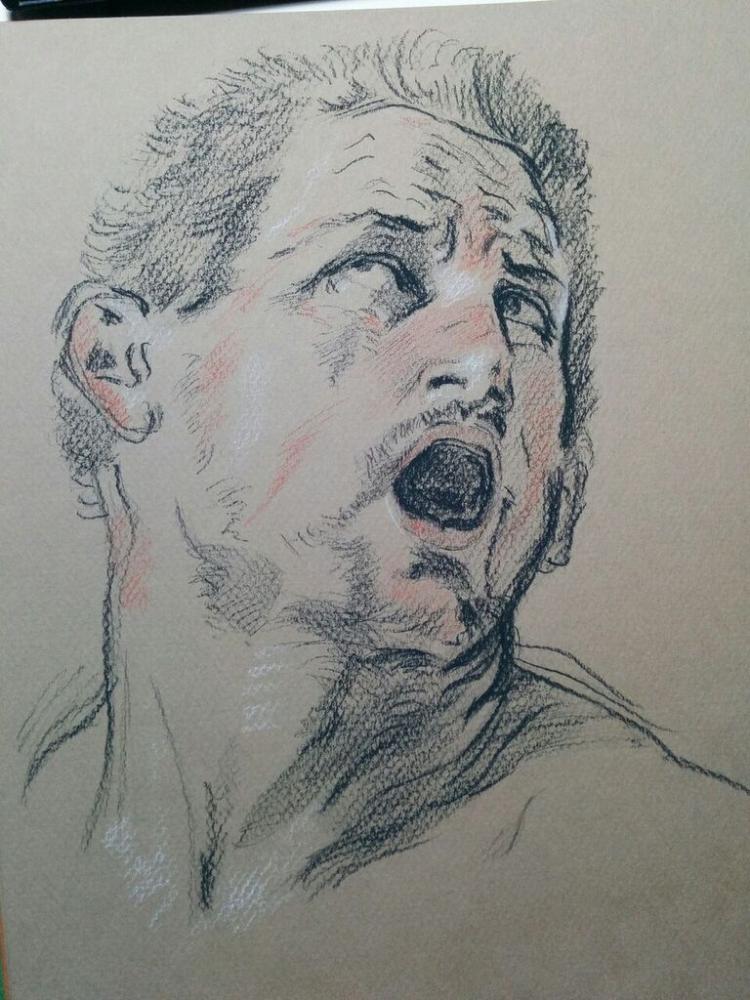

Today's drawing is taken from Guido Reni's head of a man screaming, reflecting my feelings about the need to tackle some of the work I have been ignoring.

The introduction to the excellent book Painting Techniques of the Masters succinctly puts what I have been thinking about for the last few weeks with regards to copying existing works of art to learn from them. Here it is:

Two quite separate introductions could have been written to this book. One could prove that it is dangerous and unintelligent for a young artist to absorb too much from other painters, past or present, and that the painter would do well to look only at nature and the recesses of his own mind. The second introduction could also use the history of art to prove conclusively that most painters who have made a mark in history have trained themselves largely by studying and learning from the great masters. The truth lies much nearer the second point of view than the first.Hereward Lester Cooke, Painting Techniques of the Masters

I agree. There is no need to reinvent the wheel, and there is an awful lot to be learned by seeing how better artists solved the same problems that you are faced with today. I have recently been asked on several occasions whether I am self-taught, a question which hints at the wide-spread fetish for the idea of the artist sprung from nothing, guided by pure inspiration and some kind of raw, divine, innate talent. Not only does this devalue the hard work and labour that goes in to mastering an art, but it also implicitly discourages aspiring artists from seeking help, lest they should 'taint' their natural, pure gift. This is nonsense, and I wish I had been humble enough earlier in life to take lessons from the paintings around me, rather than thinking I could go my own way unguided and somehow become the next Leonardo.

The introduction goes on:

During the seventeenth century there was a widely accepted theory that a painter should first acquire a solid groundwork of technical training, then should choose a painter from among the accepted old masters whose work particularly appealed to him, and should copy his works until he had learned the secret of this particular painter's excellence. This age produced Rembrandt, Rubens, Poussin, Guercino, Vermeer, Claude Lorrain, and a host of other great names in painting. The seventeenth-century theory, therefore, is worth careful consideration.

I have thought about it a lot and I feel strongly that the vast majority of modern and contemporary artists only do what they do because they do not have the technical ability to express themselves in another way. Technical mastery gives you the freedom to express beauty how you choose, you are not just limited to the compressed expressive range of the untrained artist. A technically proficient artist can just as easily produce an abstract, non-representational or impressionistic work as can the untrained artist, but can also produce refined beauty as well. There is a choice.

Aside from that, marvelling at the rareness of skill and the mastery of a talent is a pleasure in itself. I don't get that when I see a work of art whose merits apparently lie in its conceptual uniqueness, not the way it was crafted. If I could think of it or replicate it myself, it isn't great art. I can't replicate a Leonardo, not even after a lifetime of trying, and that is why I stand in awe of his genius.

I finished the audiobook of Ulysses today. I got more into it as it went on, finally abstracting some truths from what it says rather than how it says it. The style is as true a representation of thought as I have read, but precisely because of that I found it hard going. Anyway, here is a passage I enjoyed today, about how we imagine ourselves to be the first love our lover has ever or will ever have, even though this can only ever be manifestly untrue. One of those lovely lies we tell ourselves and does us good to believe in even if we know it to be false:

If he had smiled why would he have smiled? To reflect that each one who enters imagines himself to be the first to enter whereas he is always the last term of a preceding series even if the first term of a succeeding one, each imagining himself to be first, last, only and alone whereas he is neither first nor last nor only nor alone in a series originating in and repeated to infinity.James Joyce, Uylsses

It reminds me of how Sofia Tolstoy was heart-broken to discover the untruth of the illusion of being the first love when she read her husband's diaries. As a newly wedded teenager she wrote:

I always dreamt of the man I would love as a completely whole, new, pure person…I imagined that this man would always be with me, that I would know his slightest thought and feeling, that he would love nobody but me as long as he lived…” Sofia Tolstoy, diary entry October 8, 1862

She never forgave him for shattering her innocence.

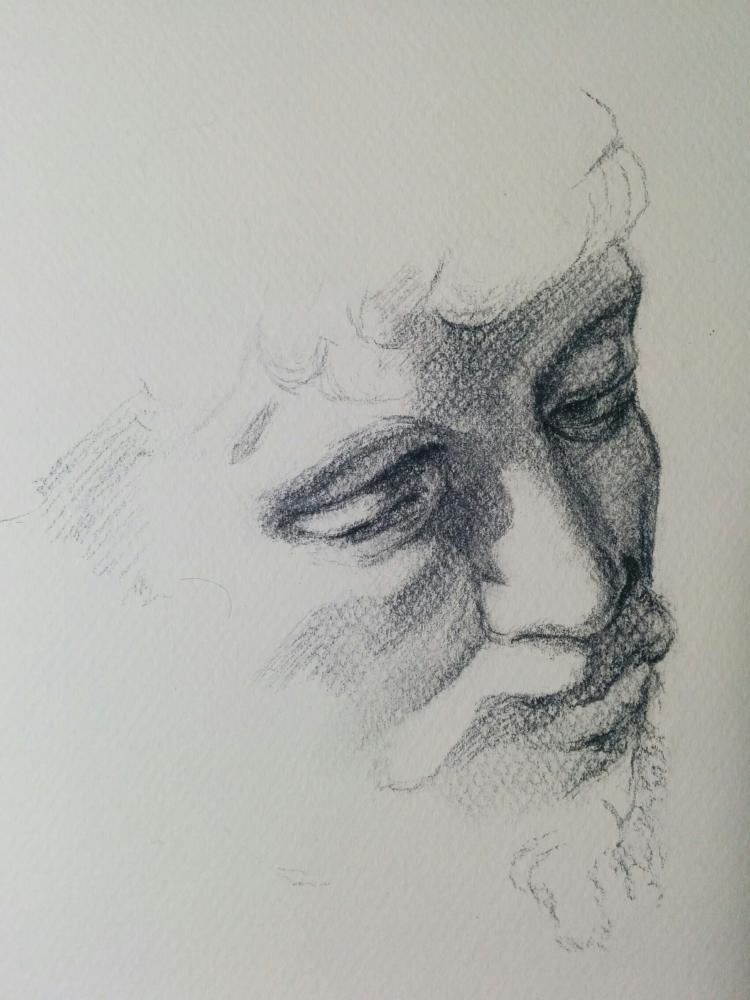

Today's study is after a drawing by Simone Cantarini that I saw last year on display at the Uffizi. It is lucky that I took a photo of it because there are no copies of it online, save for one from an obscure PDF in Italian, which will almost certainly disappear when the Uffizi update their website.

Now admittedly it is not the world's greatest drawing, and Cantarini is not a particularly famous nor well-loved artist, but it is a serene and sensitive drawing nonetheless, and I am shocked that as far as the internet is concerned it doesn't exist. Provincial galleries would be glad to have it in their collections, and I'm sure a private collector would pay good money for it. And yet, you can't find it online, and you'd be lucky to see it on display.

I feel strongly that galleries and museums should make their collections available online, under the most permissive licensing terms possible. This is where the Rijksmuseum stands out from all others -- it makes all of its high-quality images available for you to do what you like with. Isn't the mission of a good gallery or museum to encourage the widest possible enjoyment of their work? To reach new audiences? To inspire and educate? If the Uffizi burned to the ground, works like this would be lost from memory forever. Put them online, even if they are almost never seen. They will at least persist for future generations.

I think this piece would be a good teaching tool; it hasn't the complexities nor the refinement of a masterwork, but it hints at them, and helps you see the difference between what makes a work great and merely very good.

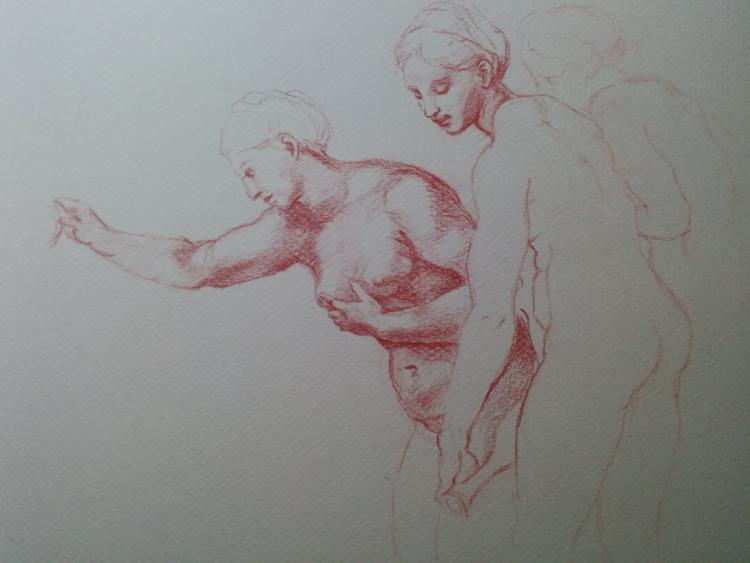

Finished off the three graces drawing this evening. It's not as accurate as I had hoped, but I don't have the energy to correct it.

In jet-lag induced bouts of wakefulness in the middle of the night I began reading Sofia Tolstoy's diaries. A lot of pain and a lot of boredom and crushed hope. Lives destined to repeat. We can read the diaries and see the problems but can we actually learn from them ourselves? In a real way, that changes our behaviour, rather than just in an intellectual way? Tolstoy read her diaries but did that change how he acted towards her? Passive cries for attention unheeded except when expedient.

Everyone thinks of changing the world, but no one thinks of changing himselfLeo Tolstoy

Tolstoy changed himself drastically over his lifetime but only in so far as was agreeable to his intellectual and spiritual aims. He was a distant, cold father to many of his children in their earliest years, and he was not infrequently a bad husband to Sofia. He hypocritically preached about chastity in marriage and other virtues he knew he did not possess. He agonized over this hypocrisy, but he didn't change himself to resolve it.

There is a piety to be found in self-loathing which salves some of the pain and discourages you from actually doing anything to improve yourself. If hating your own human weakness was an unalloyed agony it would be much easier to change, but secretly we know that rather than change ourselves for the better it is easier to ask for forgiveness for folly and indulge ourselves in whatever is the least disagreeable or least inconvenient course of action, regardless of its virtue.

I will not change my largest faults because I don't have the willpower and I can get by without doing so. I only have the motivation to do things that come easily and feed my most positive image of myself. Ultimately I spend my energy selfishly on things that don't fundamentally change who I am, even though I know what needs to be changed to make me a better person. I should be more forgiving, more open, allow myself into positions where I can be made a fool of, do things outside of my comfort zone, face up to fears, do things when I should, not put off everything, stop avoiding responsibilities, stop being bitter, jealous and self-centred, stop being a coward and think more of other people and not how they can be of use to me. Instead I pour my energies and thoughts into things I'm already good at in the vainglorious pursuit of more praise and attention.

The real masterpiece, the real work of art, should be you yourself. Perfection of an art is not a route to true happiness unless you also perfect yourself.

And because I neglect to change anything about myself, I perpetrate the same mistakes and run into the same mental ruts time and again, and never learn anything new.

Whilst thumbing through a book of master drawings I saw this study of the three graces by Raphael. I've been working slowly to make a careful copy today. It's a full-time job keeping the chalk sharp enough to try to match his line quality, and I suspect he had a studio hand sharpening his chalks for him every day.

Making a study of another work reminds you that art is the result of a process that takes time. You instantly apprehend the final result, but the artist laboured over it for many hours, constantly making decisions and adaptations that are imperceptible in the finished piece.

I have stopped before finishing so that I know where to start tomorrow. There is a lot of energy taken up in just selecting a work to begin. It's like Hemingway says of writing:

The best way is always to stop when you are going good and when you know what will happen next. If you do that every day … you will never be stuck ... That way your subconscious will work on it all the time. But if you think about it consciously or worry about it you will kill it and your brain will be tired before you start.Ernest Hemingway, Monologue to a Maestro: A High Seas Letter

Actually, reading through Hemingway's advice to aspiring writers, I think a lot of it is applicable to aspiring artists too. Below he is talking about the value of knowing what has come before so you can beat it. Know what has been done, know what is good, and compete where you can do something new and good.

Listen. There is no use writing anything that has been written before unless you can beat it. What a writer in our time has to do is write what hasnʼt been written before or beat dead men at what they have done. The only way he can tell how he is going is to compete with dead men. Most live writers do not exist. Their fame is created by critics who always need a genius of the season, someone they understand completely and feel safe in praising, but when these fabricated geniuses are dead they will not exist. The only people for a serious writer to compete with are the dead that he knows are good. It is like a miler running against the clock rather than simply trying to beat whoever is in the race with him. Unless he runs against time he will never know what he is capable of attainingErnest Hemingway, Monologue to a Maestro: A High Seas Letter

The full article is short and worth reading. There is a PDF.