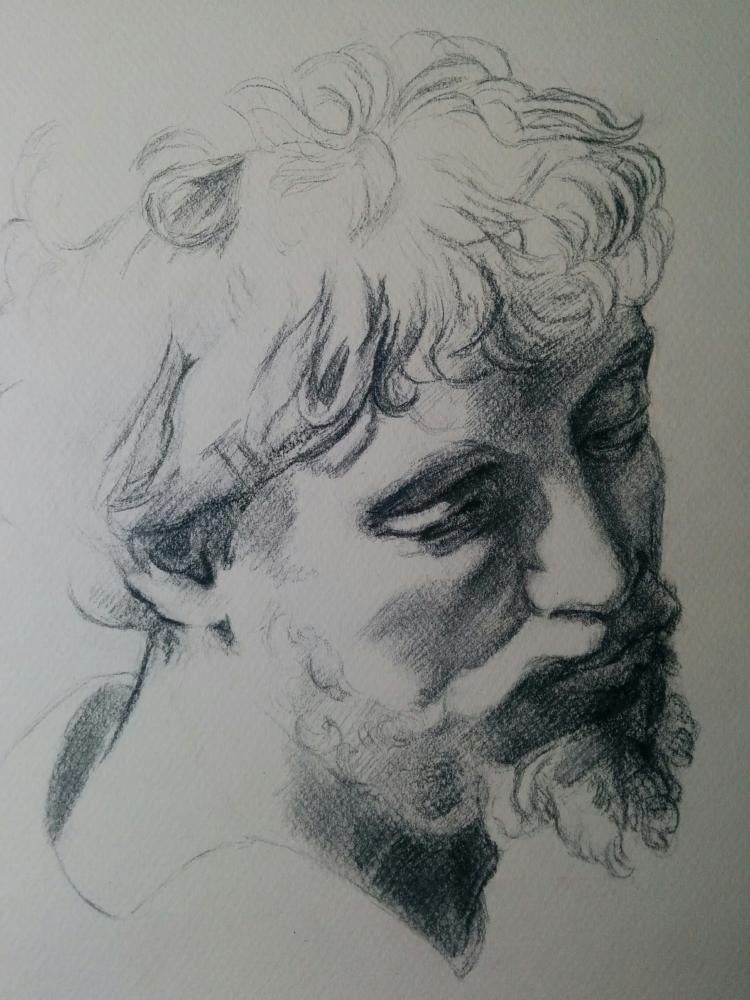

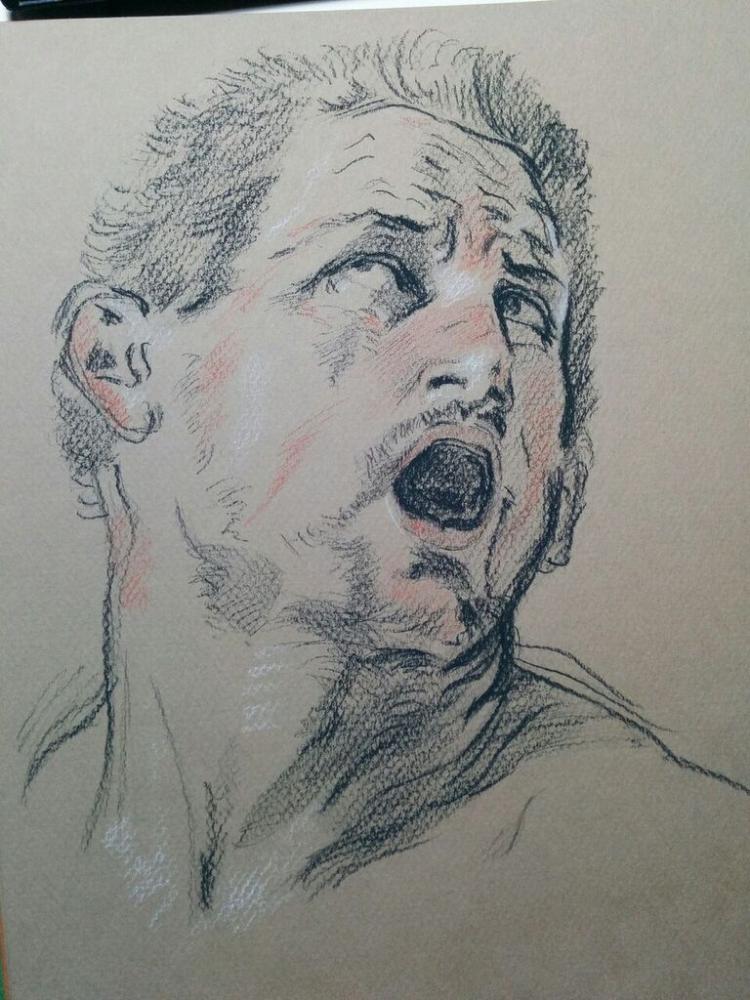

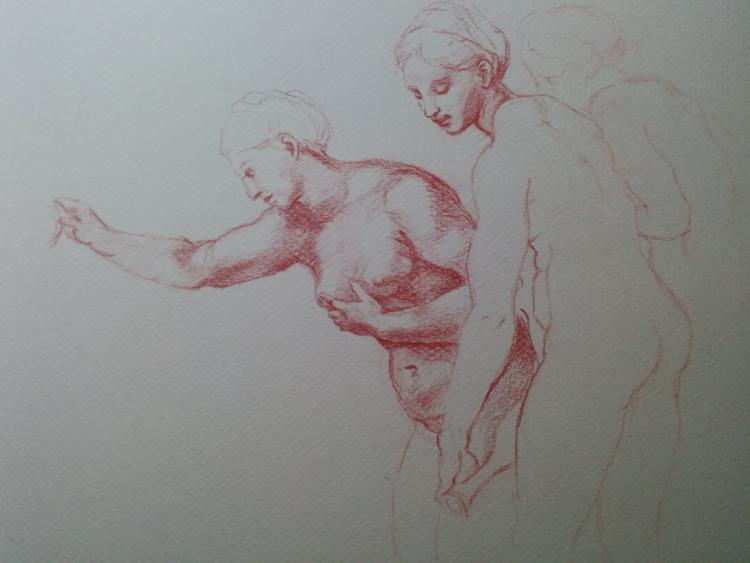

Today's drawing is taken from Guido Reni's head of a man screaming, reflecting my feelings about the need to tackle some of the work I have been ignoring.

The introduction to the excellent book Painting Techniques of the Masters succinctly puts what I have been thinking about for the last few weeks with regards to copying existing works of art to learn from them. Here it is:

Two quite separate introductions could have been written to this book. One could prove that it is dangerous and unintelligent for a young artist to absorb too much from other painters, past or present, and that the painter would do well to look only at nature and the recesses of his own mind. The second introduction could also use the history of art to prove conclusively that most painters who have made a mark in history have trained themselves largely by studying and learning from the great masters. The truth lies much nearer the second point of view than the first.Hereward Lester Cooke, Painting Techniques of the Masters

I agree. There is no need to reinvent the wheel, and there is an awful lot to be learned by seeing how better artists solved the same problems that you are faced with today. I have recently been asked on several occasions whether I am self-taught, a question which hints at the wide-spread fetish for the idea of the artist sprung from nothing, guided by pure inspiration and some kind of raw, divine, innate talent. Not only does this devalue the hard work and labour that goes in to mastering an art, but it also implicitly discourages aspiring artists from seeking help, lest they should 'taint' their natural, pure gift. This is nonsense, and I wish I had been humble enough earlier in life to take lessons from the paintings around me, rather than thinking I could go my own way unguided and somehow become the next Leonardo.

The introduction goes on:

During the seventeenth century there was a widely accepted theory that a painter should first acquire a solid groundwork of technical training, then should choose a painter from among the accepted old masters whose work particularly appealed to him, and should copy his works until he had learned the secret of this particular painter's excellence. This age produced Rembrandt, Rubens, Poussin, Guercino, Vermeer, Claude Lorrain, and a host of other great names in painting. The seventeenth-century theory, therefore, is worth careful consideration.

I have thought about it a lot and I feel strongly that the vast majority of modern and contemporary artists only do what they do because they do not have the technical ability to express themselves in another way. Technical mastery gives you the freedom to express beauty how you choose, you are not just limited to the compressed expressive range of the untrained artist. A technically proficient artist can just as easily produce an abstract, non-representational or impressionistic work as can the untrained artist, but can also produce refined beauty as well. There is a choice.

Aside from that, marvelling at the rareness of skill and the mastery of a talent is a pleasure in itself. I don't get that when I see a work of art whose merits apparently lie in its conceptual uniqueness, not the way it was crafted. If I could think of it or replicate it myself, it isn't great art. I can't replicate a Leonardo, not even after a lifetime of trying, and that is why I stand in awe of his genius.

I finished the audiobook of Ulysses today. I got more into it as it went on, finally abstracting some truths from what it says rather than how it says it. The style is as true a representation of thought as I have read, but precisely because of that I found it hard going. Anyway, here is a passage I enjoyed today, about how we imagine ourselves to be the first love our lover has ever or will ever have, even though this can only ever be manifestly untrue. One of those lovely lies we tell ourselves and does us good to believe in even if we know it to be false:

If he had smiled why would he have smiled? To reflect that each one who enters imagines himself to be the first to enter whereas he is always the last term of a preceding series even if the first term of a succeeding one, each imagining himself to be first, last, only and alone whereas he is neither first nor last nor only nor alone in a series originating in and repeated to infinity.James Joyce, Uylsses

It reminds me of how Sofia Tolstoy was heart-broken to discover the untruth of the illusion of being the first love when she read her husband's diaries. As a newly wedded teenager she wrote:

I always dreamt of the man I would love as a completely whole, new, pure person…I imagined that this man would always be with me, that I would know his slightest thought and feeling, that he would love nobody but me as long as he lived…” Sofia Tolstoy, diary entry October 8, 1862

She never forgave him for shattering her innocence.